Image from www.metmuseum.org

In a museum as large as the Met, it’s easy to overlook this piece. It sits in one of the many maze-like galleries that flank the main hall of the Greek and Roman wing. On the day I visited the Met, it had been raining all morning and was cloudy and grey outside. After wandering through the windowless corridors of the museum’s interior, I made my way into the Greek and Roman arts section and was pleasantly surprised to find myself greeted by bright rays of sunshine coming through the glass arched ceiling.

If you happen to enter gallery 156 from the main hall, you probably won’t notice this piece. The gallery is full of display cases, showing off immaculately painted Greek pottery. There’s a life size sculpture of a kneeling lion that greets you and seems to dominate the room, and another more prominently displayed stele looks out over the gallery. However, if you happen to enter the room from the neighboring gallery (number 155), this sculpture will be the first thing you see. It is positioned in such a way that it faces that entryway, but a dividing wall behind it blocks the view of it from the main hall.

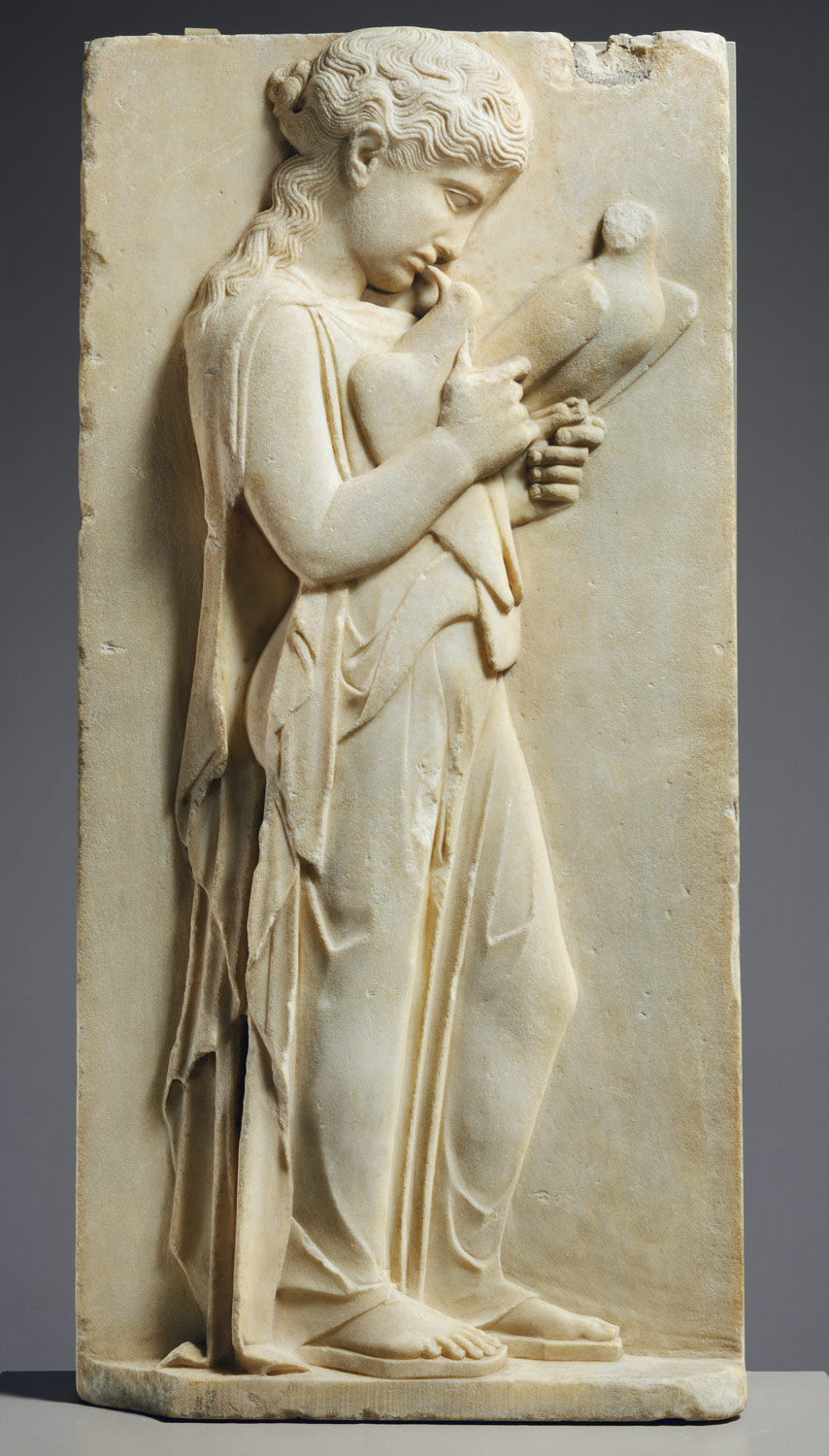

My attention was captured by this beautiful stone carving of a little girl. She looked so sweet, with her head bent down to kiss one of her birds. Upon reading the plaque beside the piece, I learned that this stele had actually been carved as a grave marker, presumably for the child depicted. I felt so much emotion after reading that plaque. I imagined her alive and playing with her pet birds. I also imagined the grief her parents felt, and their desire to honor her memory after death by commissioning this sculpture. I felt such a strong connection to this piece, and I instantly I knew that I wanted to research and get to know more about it.

The stele measures just under 3 feet tall. The sculpture is carved in relief, with the figures having been hewn out of a single slab of Parian Marble. Named for the Greek island of Paros where it was quarried, Parian Marble was highly prized for its uniform white color and its translucent qualities. The sculptor of this piece showed immense attention to detail, it is particularly expressed in the sophisticated carving of the subject’s hair. The fine lines that make up her strands of hair are so intricate that they look almost like ripples on the surface of a pool of water. She is depicted wearing a woolen Greek tunic known as a peplos, which falls slightly open on her side. The sculptor managed to carve her peplos in such a way that it looks gauzy and lightweight, making the outline of her body and her stance clearly visible to the viewer.

In this sculpture we see a simple composition consisting of a single primary figure. The solitary figure takes up nearly all available space on the marble slab. The figure is carved in a slightly off center position and the sculptor has chosen to leave some space on both the right and left sides blank. We can also see that the sculptor has carved out the base of the piece in a way that enhances the three dimensional aspect of the piece. The perfectly smooth and monochromatic marble serves as an ideal medium to carve this image out of.

The subject of this sculpture is a young girl. We can see that she is not an adult by her shortened stature and her petite limbs and fingers. Her head is also slightly over sized in proportion to her body. She is shown holding a pair of birds. She nods her head down and presses her lips against the beak of one of the birds, while the other perches gracefully on her fingertips. It’s impossible for us to know what her cause of death may have been, but whoever commissioned this piece wanted her to be remembered as a happy and playful child. A grave marker such as this was a highly personal piece, and based on the quality of the sculpture and the material, we can assume that the subject belonged to a wealthy family.

This marble stele was carved sometime between 450-440 BCE on the island of Paros, Greece. It is one of the earliest known stelae that commemorates the death of a child. In this composition the girl is the sole figure, clearly identifying her as the deceased person. In later stelae, children begin to be incorporated in various compositions, sometimes shown alone and other times shown accompanied by a parent (usually the mother) or a nurse. In some cases, children were included on stelae of other relatives simply for the purpose of showing their role as a member of the family unit, not because they had passed on.

This marble stele was carved sometime between 450-440 BCE on the island of Paros, Greece. It is one of the earliest known stelae that commemorates the death of a child. In this composition the girl is the sole figure, clearly identifying her as the deceased person. In later stelae, children begin to be incorporated in various compositions, sometimes shown alone and other times shown accompanied by a parent (usually the mother) or a nurse. In some cases, children were included on stelae of other relatives simply for the purpose of showing their role as a member of the family unit, not because they had passed on.

The stele was discovered on Paros in 1785. It was part of the collection of Sir Richard Worsley from that time up until the early nineteenth century. The piece was first documented and illustrated by Worsley in 1794. Later in the 19th century it was purchased by the Earl of Yarborough. The Metropolitan Museum acquired the piece in 1927 when it was purchased from the Fourth Earl of Yarborough. Prior to being put on display at the Met, this piece had lived in quiet English country homes and was rarely seen by the outside world.

The Greek victory over the Persian Empire in 480 BCE marked the start of the Classical period. Many strides were made during this time in the realms of science, mathematics, and philosophy. A new artistic style was ushered in that contrasted noticeably from the Archaic style which preceded it. In a departure from the “Archaic smile,” the expressions of Greek figures began to express pathos, or emotion. Sculptors like Polykleitos (known for the often copied “Doryphoros” or “Spear Bearer”) were pursuing perfection in trying to capture human proportions. In the mid 5th century BCE, the Athenian leader Pericles ordered the reconstruction of the Athenian Acropolis, which had been destroyed by the Persian army in 480 BCE. Construction on one of the most famous structures of the ancient world, the Temple of Athena Parthenos (better known as the Parthenon), lasted from 447-438 BCE.

At the time, Greece was composed over several independent city-states, one of which was the island of Paros. Paros grew wealthy from the export of it’s high quality marble. Parian marble was highly prized in the ancient world and was used for some of the most iconic classical Greek sculptures, including the famous Venus de Milo.

Hellenic society valued humankind in a way that no other society had before. The Greeks are credited with the invention of democracy, or rule by the people (demos). It is important to note that this concept of a democratic society mostly applied to well-born men; women were largely excluded from participating in society and the practice of slavery was widespread.

In the patriarchal society of Ancient Greece. Women were controlled by their fathers until they were old enough to marry, at which point a dowry would have been paid that transferred their possession to their husbands. Noble women were seldom allowed to leave their quarters and were forbidden from attending banquets and symposiums with men (although prostitutes and slaves were allowed to do so.) There were some religious rituals that women were allowed to attend, including some that were specifically tailored to young girls. In one ritual dedicated to the goddess Artemis, girls as young as five would be chosen to play the role of “little bears,” wild animals that could only be tamed through marriage.

In the patriarchal society of Ancient Greece. Women were controlled by their fathers until they were old enough to marry, at which point a dowry would have been paid that transferred their possession to their husbands. Noble women were seldom allowed to leave their quarters and were forbidden from attending banquets and symposiums with men (although prostitutes and slaves were allowed to do so.) There were some religious rituals that women were allowed to attend, including some that were specifically tailored to young girls. In one ritual dedicated to the goddess Artemis, girls as young as five would be chosen to play the role of “little bears,” wild animals that could only be tamed through marriage.

Members of Hellenic society worshiped a pantheon of gods and goddesses. They also had a very clear conception of the afterlife. They believed that at the moment of death, the spirit left the body and began its journey into the underworld. The underworld was the domain of the god Hades, a brother of Zeus. Hades ruled over the souls of the dead with his wife Persephone at his side. It had never been seen as a pleasant place, it was mostly considered to be a realm of darkness and misery. All mortals were subject to the same fate, be they rich or poor, villains or heroes.

Ancient Greeks had a series of burial rites which they believed to be essential to honoring the memory of a deceased person. These rituals, typically consisting of a three part process, were most commonly performed by female members of the deceased. In the first part of the ritual, the body was washed, anointed with oil, and then laid out in a place of prominence in the house. Relatives and friends would then come over to mourn the dead, in a way similar to our modern pre-funeral wakes. The body was then led to the cemetery, often accompanied by a funerary procession. After burial, the grave sites would be topped by marble stelae or statues, depending on whether or not the family had the financial means to do so.

The grave markers typically featured a relief depicting a likeness of the deceased person. They would usually be shown along with a chosen attribute, which could have included a favorite pet, a servant, a musical instrument, or any other prized possession. Like all other sculptures in the ancient world, these funerary stelae and statues would have been painted in bright colors (although to our modern eyes, the simplicity of the marble itself might appear more sophisticated.) Although no traces of the paint remain today, historians are able to identify elements of this artwork that would have been illustrated using paint. Some examples of these would have been the eyes of the girl and the birds and the leather straps of her sandals. The stele would have also been topped by an ornamental carving known as a akroterion. Although it is lost to history, the holes where the akroterion would have been attached can still be seen on the top of the stele. In its original finished state, the stele would have looked similar to another work known as the Giustiniani Stele, which is currently in the collection of the Berlin State Museums in Germany. The Giustiniani Stele is believed to be slightly older than the grave stele of the little girl, but it is also believed to have originated from Paros.

The Grave Stele of a Little Girl bears a resemblance to another piece, the Grave Stele of Hegeso, ca. 400 BCE. This stele commemorates the death of Hegeso, a well-to-do Athenian woman. We are able to identify the woman as Hegeso because her name, along with that of her father Proxenos, was carved into the cornice of the pediment of the stele. In a style similar to the little girl, Hegeso is shown with attributes that she may have cherished during the time she was alive. While the girl is shown with her humble pet birds, Hegeso is shown admiring a box of jewelry held by a servant girl. At the time, the servant would have been considered property, not unlike the jewelry her gaze rests upon. The irony lies in the fact that Hegeso would not have had much more freedom than her servant.

Despite the fact that this work of art is more than 2,000 years old, we can still find many similarities between the society that made it and our own. Many of our modern concepts of government and democracy were born in Ancient Greece. The style of grave marker popular during the Classical period bears a striking similarity to modern funerary monuments. Recent trends have even seen people engraving photographs of their deceased loved ones on tombstones. Although the little girl depicted on this stele died long ago, her memory has lived on for centuries through this beautiful work of art.

Sources:

- Neils, Jenifer, et al. Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. Yale University Press in Association with the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, 2003. pp. 73-75

- Worsley, Richard. 1794. Museum Worsleyanum; or, A Collection of Antique Basso Relievos, Bustos, Statues and Gems, Vol. 1. pl. 35, London: From the Shakespeare Press by W. Bulmer & Company.

- Clark, James A. “The Marble Island Of Paros, Quiet Heart Of the Cyclades.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 4 June 1978, www.nytimes.com/1978/06/04/archives/the-marble-island-of-paros-quiet-heart-of-the-cyclades-a-maternal-a.html.

- Hemingway, Colette. “Women in Classical Greece.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wmna/hd_wmna.htm (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dbag/hd_dbag.htm (October 2003)

- Gisela M. A. Richter. “A Greek Relief.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 22, no. 4, 1927, pp. 101–105. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3256011.

- Boardman, John. The Cambridge Ancient History: V.5a-6a: Plates to Volumes V and VI: the Fifth and Fourth Centuries, B.C. Cambridge University Press, 1994. pp 16

- Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art through the Ages 13th Ed. V.1. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2006.pp 120

Comments

Post a Comment